The bottle held a thin broth, light brown, with some uncertain chunks of dark matter bobbing on top-a soup, maybe, but one that you'd never want to eat. Once it was poured into a white plastic tray, the chunks resolved into insects. Here were butterflies and moths, the delicate patterns of their wings dimmed after a week or two in ethanol. Here were beetles and bumblebees and lots of burly-looking flies, all heaped together, plus a bevy of large wasps, their stripes and stingers still bright.

Michael Sharkey took out a pair of thin forceps and began examining his catch. It included anything small and winged that lived in the meadows and forests around his house, high in the Colorado Rockies, and that had suffered the misfortune, in the previous two weeks, of flying into the tent-shaped malaise trap he had erected in front of his home and we had emptied earlier that morning.

Though Sharkey is a hymenopterist, an expert on the insect order that includes wasps, he ignored the obvious stripes and stingers. He ignored, in fact, all of the creatures the average person might recognize as wasps-or even recognize at all. Instead, he began pulling little brown specks out of the soup, peering at them through a pair of specialized glasses with a magnifying loupe of the sort a jeweler might wear. Dried off and placed under the microscope on his desk, the first speck revealed itself to be an entire, perfect insect with long, jointed antennae and delicately filigreed wings. This was a braconid wasp, part of a family of creatures that Sharkey has been studying for decades. Entomologists believe that there are tens of thousands of species of braconid sharing this planet, having all sorts of important impacts on the environments around them. But most humans have probably never heard of them, much less been aware of seeing one. Huge parts of the braconid family tree are, as the saying goes, still unknown to science.

This story is from the December 2022 - January 2023 edition of WIRED.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the December 2022 - January 2023 edition of WIRED.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

MOVE SLOWLY AND BUILD THINGS

EVERYTHING DEPENDS ON MICROCHIPS-WHICH MEANS TOO MUCH DEPENDS ON TAIWAN. TO REBUILD CHIP MANUFACTURING AT HOME, THE U.S. IS BETTING BIG ON AN AGING TECH GIANT. BUT AS MONEY AND COLOSSAL INFRASTRUCTURE FLOW INTO OHIO, DOES TOO MUCH DEPEND ON INTEL?

FOLLOW THAT CAR

CHASING A ROBOTAXI FOR HOURS AND HOURS IS WEIRD AND REVELATORY, AND BORING, AND JEALOUSY-INDUCING. BUT THE DRIVERLESS WORLD IS COMING FOR ALL OF US. SO GET IN AND BUCKLE UP.

REVENGE OF THE SOFTIES

FOR YEARS, PEOPLE COUNTED MICROSOFT OUT. THEN SATYA NADELLA TOOK CONTROL. AS THE COMPANY TURNS 50, IT'S MORE RELEVANT-AND SCARIER-THAN EVER.

THE NEW COLD WARRIOR

CHINA IS RACING TO UNSEAT THE UNITED STATES AS THE WORLD'S TECHNOLOGICAL SUPERPOWER

CALIFORNIA DREAMIN'

KINDRED MOTORWORKS VW BUS - Despite being German, the VW T1 Microbus is as Californian as the Grateful Dead.

THE INSIDE SCOOP ON DESSERT TECH

A lab in Denmark works to make the perfect ice cream. Bring on the fava beans?

CONFESSIONS OF A HINGE POWER DATER

BY HIS OWN estimation, JB averages about three dates a week. \"It's gonna sound wild,\" he confesses, \"but I've probably been on close to 200 dates in the last year and a half.\"

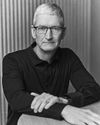

THE WATCHFUL INTELLIGENCE OF TIM COOK

APPLE INTELLIGENCE IS NOT A PLAY ON \"AI,\" THE CEO INSISTS. BUT IT IS HIS PLAY FOR RELEVANCE IN ALL AREAS, FROM EMAIL AUTO-COMPLETES TO APPS THAT SAVE LIVES.

COPYCATS (AND DOGS)

Nine years ago, a pair of freshly weaned British longhair kittens boarded a private plane in Virginia and flew to their new home in Europe.

STAR POWER

The spirit of Silicon Valley lives onat this nuclear fusion facility's insane, top-secret opening ceremony.