To appreciate “Home,” Samm-Art Williams’s celebrated play from 1979, is, in part, to be drawn back in time, to the heyday of the Negro Ensemble Company, headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1967, it was a crucial hotbed for Black writing, acting, and directing talent, helping to produce names like Phylicia Rashad, Samuel L. Jackson, Esther Rolle, and Denzel Washington. Williams—who died in May, mere days before “Home” ’s revival on Broadway, at Roundabout’s Todd Haimes Theatre, under Kenny Leon’s direction—was a mainstay of the company.

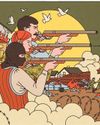

Williams was a big man—six-six and around three hundred pounds, according to his friends—funny and kind. Like Cephus (Tory Kittles), the blithe, antic, tricksterish protagonist of “Home,” he was from a small town in North Carolina, called Burgaw. Cephus’s is called Cross Roads. Williams got the idea for the play on a Greyhound bus headed to the South from his new home, New York. Like many Black plays of the era, “Home” issues forth from the twin themes of migration and political alienation. Cephus is a down-home guy, a farmer deeply connected to the country soil. He’s in love with Pattie Mae (Brittany Inge), the sweetheart of his youth, who goes off to college and gets too full of book learning to feel comfortable returning to Cross Roads. Cephus’s long-held hope to marry her is dashed.

Soon, Cephus ducks the Vietnam draft and does time in prison, then reluctantly skips town and heads north, to the coldhearted streets of New York. The speech in “Home” resembles a cycle of lyric poems voiced by high-minded, plain-living folk. Inge and Stori Ayers play a host of characters, sometimes a confirming chorus and sometimes a panoply of tempters and sidekicks, giving Cephus’s journey shades of an epic allegory. The dialogue is full of effusions such as this one, from Cephus:

This story is from the June 17, 2024 edition of The New Yorker.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the June 17, 2024 edition of The New Yorker.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

GET IT TOGETHER

In the beginning was the mob, and the mob was bad. In Gibbon’s 1776 “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” the Roman mob makes regular appearances, usually at the instigation of a demagogue, loudly demanding to be placated with free food and entertainment (“bread and circuses”), and, though they don’t get to rule, they sometimes get to choose who will.

GAINING CONTROL

The frenemies who fought to bring contraception to this country.

REBELS WITH A CAUSE

In the new FX/Hulu series “Say Nothing,” life as an armed revolutionary during the Troubles has—at least at first—an air of glamour.

AGAINST THE CURRENT

\"Give Me Carmelita Tropicana!,\" at Soho Rep, and \"Gatz,\" at the Public.

METAMORPHOSIS

The director Marielle Heller explores the feral side of child rearing.

THE BIG SPIN

A district attorney's office investigates how its prosecutors picked death-penalty juries.

THIS ELECTION JUST PROVES WHAT I ALREADY BELIEVED

I hate to say I told you so, but here we are. Kamala Harris’s loss will go down in history as a catastrophe that could have easily been avoided if more people had thought whatever I happen to think.

HOLD YOUR TONGUE

Can the world's most populous country protect its languages?

A LONG WAY HOME

Ordinarily, I hate staying at someone's house, but when Hugh and I visited his friend Mary in Maine we had no other choice.

YULE RULES

“Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point.”