It was the roaring twenties when Charlie Chaplin's first serious drama, A Woman of Paris, had its premiere in Los Angeles. The women wore pearls and flapper dresses, the men crisp suits and Panama hats as they strolled along the bustling pavements of Hollywood in its golden age. Chaplin had a string of comedy triumphs behind him, including Easy Street (1917), The Immigrant (1917) and The Kid (1921), and the stage was set for his ambitious next project.

But things did not go quite to plan. Though it was a hit with the critics, A Woman of Paris left audiences in Los Angeles feeling somewhat bemused on its 1923 debut. They had expected another comedy, a film with Chaplin as the star, and instead they got a rather dark drama where he appears only in a cameo role. Chaplin had, to some extent, anticipated this response and arranged for flyers to be distributed at the premiere to warn the audience that this work diverged somewhat from his previous films. But he was still stung by the cool reception. Although the film eventually made a decent profit, it was not nearly as popular as his comedies.

Chaplin put the setback behind him and went on to make comedy greats such as City Lights (1931), Modern Times (1936) and The Great Dictator (1940), but he never gave up on A Woman of Paris. In 1976, just a year before his death, he reissued an edited version of the film with a new musical score that turned out to be the last work he would ever complete.

This story is from the Christmas 2023 edition of BBC Music Magazine.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the Christmas 2023 edition of BBC Music Magazine.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

A way with words

Great operas are inextricably linked with their composer but, asks Jessica Duchen, how often do we acknowledge the important role of the librettist?

THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN Pick a theme... and name your seven favourite examples

Conductor Domingo Hindoyan nominates the best musical depictions of anger and frustration

A glittering beacon

Until its destruction in the fire of 1936, the Crystal Palace was one of the world's most exciting music venues, and its legacy still lives on today, writes Tom Service.

Christoph Willibald Gluck

Paul Riley traces the wandering existence of a cosmopolitan composer who made it his life's work and ambition to rip up opera's rulebook

The Awards are upon us once more!

Time to vote for the best recordings of the last 12 months

LEADING FROM THE FRONT

From running efficient rehearsals to learning to speak to orchestras with clarity and empathy, an array of exciting courses for conductors has bloomed in recent years, finds Clare Stevens

Kindred spirits

As their second opera takes to the stage, composer Gregory Spears and librettist Tracy K Smith talk to Charlotte Smith about their special partnership

The censors' refusal to play ball drives Verdi to despair

In the early months of 1857, Verdi had Shakespeare on his mind, and specifically King Lear.

11 Bed-Hopping Composers

Jeremy Pound lifts the covers off those notorious notesmiths who found the thrill of playing away simply too hard to resist

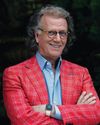

André Rieu Violinist, Conductor

King of the Waltz, Dutch musical impresario André Rieu has taken the world by storm with his Johann Strauss Orchestra.