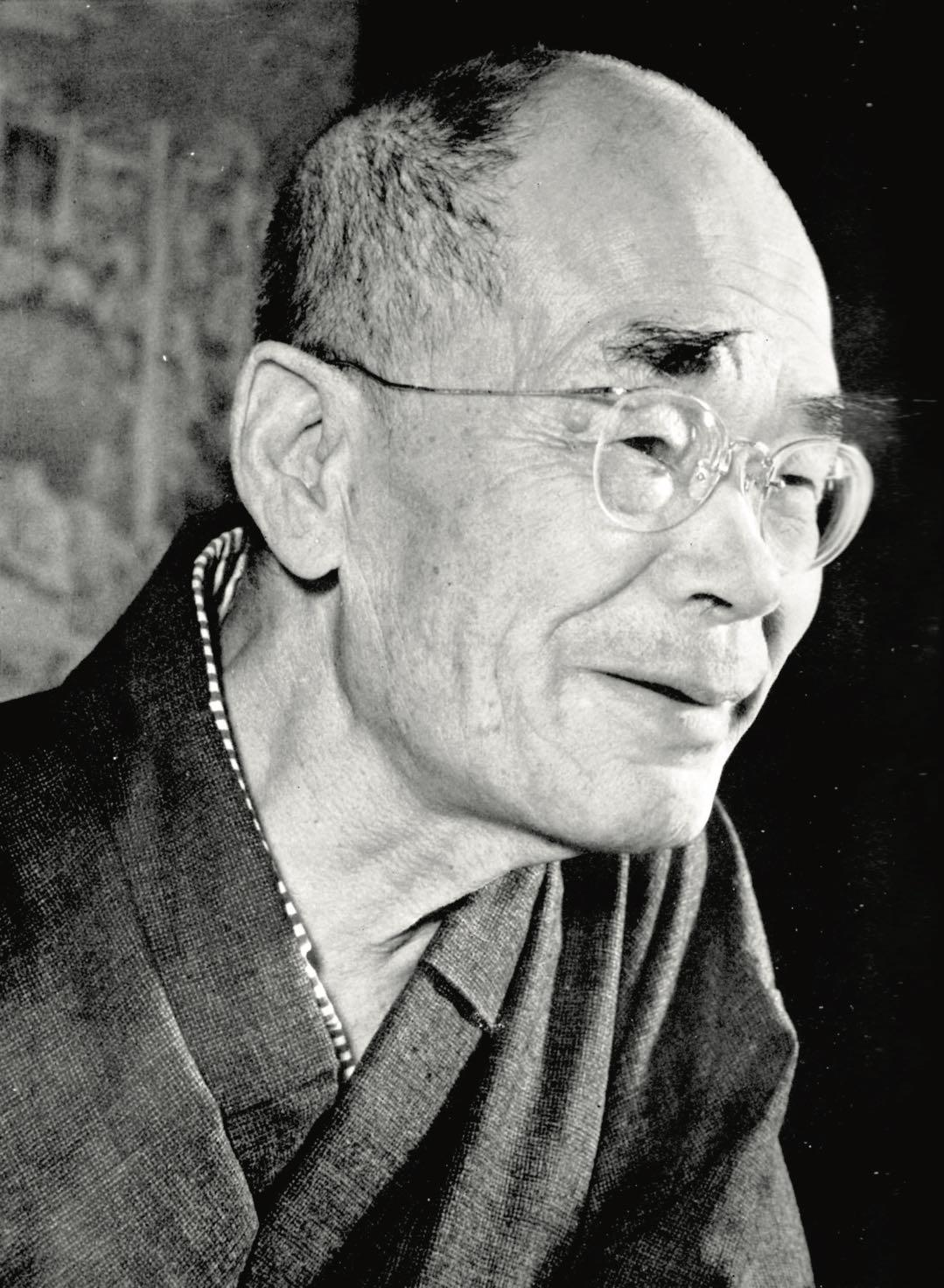

According to Christmas Humphreys, the founder in 1924 of the Buddhist Society in London, Zen Buddhism is the 'apotheosis' - the divine culmination - of Buddhism. Humphreys on to describe Zen as a practical, non-intellectual method of directly experiencing 'ultimate reality'. If so, then Zen should be of interest to phenomenologists, Kantians and all the other Western philosophers who have argued about our ability to apprehend reality. But was he right? Humphreys derived most of his ideas about Zen from his friend, the Japanese scholar Daisetsu T. Suzuki (1870-1966), who has been well described as the man who brought Zen to the West.

Perhaps the best-known Japanese philosopher of the twentieth century, Suzuki was born into a Samurai family in Northern Japan in 1870. After a brief period studying at what is now Waseda University in Tokyo, Suzuki became a disciple of Zen master Shaku Soen (1859-1919), and spent five years undergoing Rinzai Zen training at the famous Engakuji Monastery in Kamakura. He is said to have become enlightened in 1895.

In 1893 Suzuki accompanied Shaku Soen to the renowned World Parliament of Religions held in Chicago. Four years later he was invited to the United States to work as a translator for the philosopher and publisher Paul Carus. What is of interest is that Carus had been a student of Schopenhauer, whose ethics features many Buddhist ideas, and was also an early advocate of panpsychism (which means 'mind everywhere'), which is currently fashionable in academic philosophy of mind.

Suzuki spent eleven years in the United States, between 1897-1908, and developed a deep interest in Western philosophy, Christian mysticism, and comparative religion. He came to write important studies of the German Neoplatonist Meister Eckhart, and the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, emphasizing the close affinities between Christian mysticism and Mahayana Buddhism (of which Zen is a branch).

This story is from the August/September 2022 edition of Philosophy Now.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the August/September 2022 edition of Philosophy Now.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

Metaphors & Creativity

Ignacio Gonzalez-Martinez has a flash of inspiration about the role metaphors play in creative thought.

Medieval Islam & the Nature of God

Musa Mumtaz meditates on two maverick medieval Muslim metaphysicians.

Robert Stern

talks with AmirAli Maleki about philosophy in general, and Kant and Hegel in particular.

Volney (1757-1820)

John P. Irish travels the path of a revolutionary mind.

IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE

Becky Lee Meadows considers questions of guilt, innocence, and despair in this classic Christmas movie.

"I refute it thus"

Raymond Tallis kicks immaterialism into touch.

Cave Girl Principles

Larry Chan takes us back to the dawn of thought.

A God of Limited Power

Philip Goff grasps hold of the problem of evil and comes up with a novel solution.

A Critique of Pure Atheism

Andrew Likoudis questions the basis of some popular atheist arguments.

Exploring Atheism

Amrit Pathak gives us a run-down of the foundations of modern atheism.